Liverwort Life Cycle

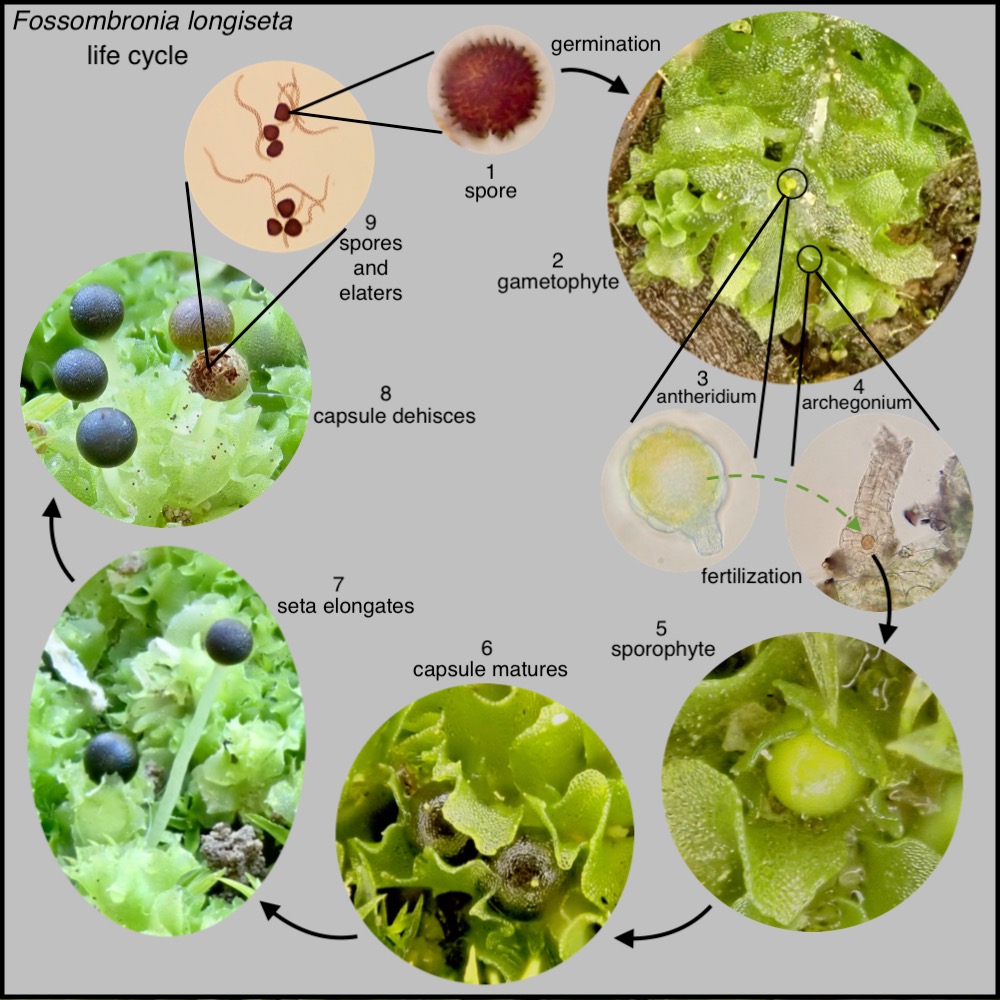

All liverwort species exhibit the same general life cycle, alternating between two generations: the gametophyte (the part of the plant that makes the gametes – sperm and eggs), and the sporophyte (the part of the plant that makes the spores). Liverworts are extremely diverse morphologically, and no single species is representative of the whole group. I’ve chosen to illustrate the life cycle with Fossombronia longiseta, a simple thallose liverwort (albeit a “leafy” one), because all of the parts are easily seen. For an example of a complex thallose liverwort, see Cryptopmitrium tenerum at the bottom of this page.

Scroll down for enlarged photos with detailed explanations.

1. A spore blows in the wind and lands in a suitable habitat.

2. The spore germinates and develops into the gametophyte, the part of the plant that makes the gametes: the sperm and eggs. In Fossombronia longiseta, the gametophyte consists mainly of a stem with leaves, and with rhizoids which attach the plant to the substratum. The male and female organs can be seen naked on the stem. On the plant in this photo, there are only a few antheridia. More often than not, the stem will be covered with antheridia (see photo below). Archegonia are much more difficult to spot.

3. The male reproductive organs, antheridia, develop on the dorsal surface of the stem of Fossombronia longiseta. The yellow/orange spherical antheridia can be seen nestled amongst the lettuce-like leaves.

3. Each antheridium contains thousands of sperm. Upon their release, sperm must swim through liquid water to a nearby archegonium to fertilize the egg.

4. The female reproductive structures, archegonia, also develop on the dorsal surface of the stem of Fossombronia longiseta. These are not visible with the naked eye but can be detected with a high power hand lens and can be seen clearly here through the microscope magnified 400x. Sperm must swim through liquid water from the antheridium to an archegonium, and down the neck to fertilize the egg.

5. Once fertilized, the egg becomes a diploid zygote, which divides and develops into the sporophyte, the part of the plant that makes the spores. The green sphere in the center of this photo is a Fossombronia longisetasporophyte capsule in the early stages of development. The neck of the archegonium can still be as a nub on the top of the sphere.

6. The sporophyte capsule remains nestled amongst the leaves until the spores within it have matured. At this point, the capsule darkens from green to black. In this photo, the remainders of the archegonium necks can be seen as green nubs atop the two black maturing capsules.

7. The sporophyte consists of a simple capsule, as well as a foot and a seta (the latter two lacking in some liverwort species). The capsule contains the developing spores. Upon completion of spore development, the seta extends, raising the sporophyte capsule above the gametophyte. This occurs rapidly through water imbibition and by cell elongation rather than cell division. The seta is thus a very weak and transient structure resembling a glass noodle.

8. The sporophyte capsule then opens in a rather simple manner to release the spores. In most liverwort species this occurs along 4 or sometimes 2 lines of dehiscence, like a banana peel. In the case of Fossombronia longiseta and some other liverwort species, it occurs in a more irregular fashion.

9. The sporophyte capsules of most liverwort species contain elaters, spring-like cells which assist in spore dispersal. This is one of the unifying features of liverworts, though some species lack elaters. In contrast, mosses never have elaters and hornworts have pseudoelaters.

10./1. The spore will then fly off into the wind to begin the life cycle once again.

Elevated archegoniophores on complex thallose liverworts

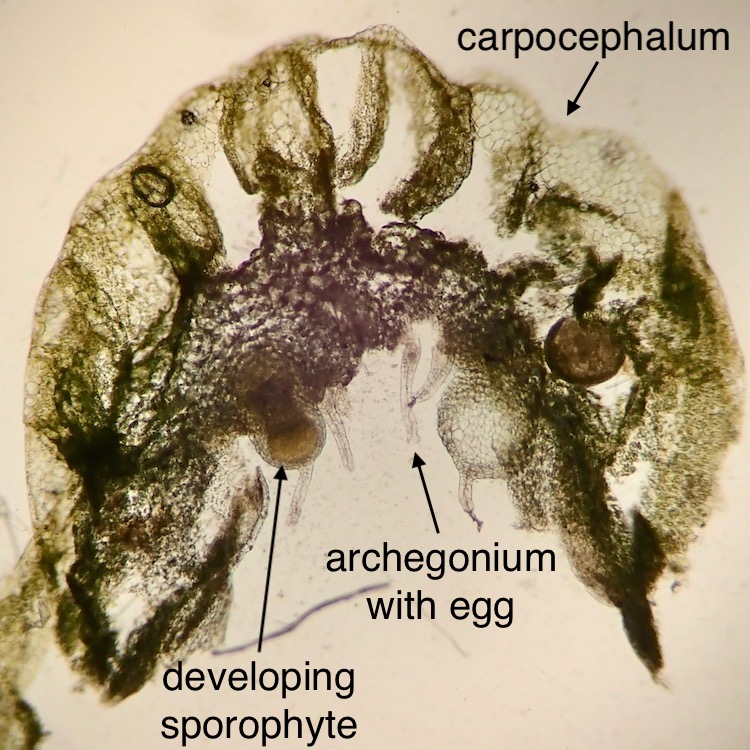

Many complex thallose liverworts have additional elevated structures called archegoniophores, which may be mistaken for sporophytes, but are in fact part of the gametophyte. Archegoniophores contain archegonia, the female reproductive structure seen in the example above. In this case, the archegonia are hanging upside-down within the umbrella top or carpocephalum (see cross-section below).

This photomicrograph of a cross-section of a Cryptomitrium tenerum carpocephalum shows an archegonium with an unfertilized egg dangling upside down. The bulging archegonium on the left contains what was once a fertilized egg and is now developing into a sporophyte, also dangling upside down.

Upon maturation, the shiny black sporophyte capsules of Cryptomitrium tenerum are visible peeking out from the underside of the carpocephala.