- How can you tell a liverwort from a moss?

- How can you tell a liverwort from a hornwort?

- How can you tell a liverwort from a lichen?

- Do animals eat bryophytes?

- Are there any non-native or invasive bryophytes?

- Do bryophytes harm the trees they grow on?

- Do bryophytes function like a biological crust?

How can you tell a liverwort from a moss?

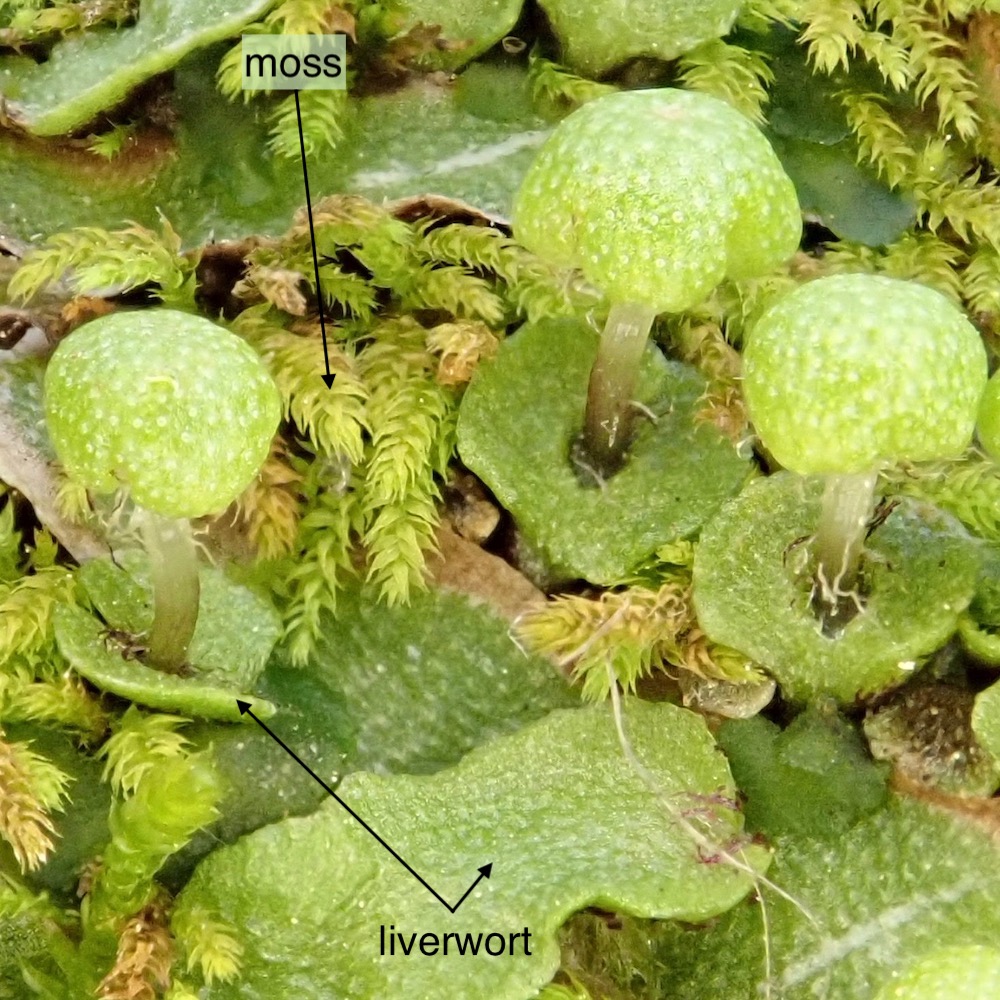

Mosses have stems with leaves, typically arranged in a spiral around the stem, which may be upright or prostrate. Many liverworts do not have stems or leaves; instead, they have a thallus, which has a distinct upper and lower surface and is generally prostrate.

This photo shows the complex thallose liverwort, Asterella bolanderi, surrounded by mosses with distinct leaves along stems.

This photo shows the bottlepore liverwort, Sphaerocarpos texanus growing amongst the moss Timmiella, its long lanceolate leaves spirally arranged around the rather short stem.

Leafy liverworts can be more difficult to differentiate from mosses. Leafy liverworts have a stem with two rows of leaves on either side, sometimes with an additional row of smaller leaves underneath. Leafy liverworts often have a flattened appearance, as demonstrated by the Porella bolanderi in this photo.

In addition to generally being arranged spirally around the stem, the leaves of most moss species have a line down the middle called a midrib, or costa, as seen on the Syntrichia species in this photo. In contrast, the leaves of leafy liverworts never have a midrib.

In addition, the leaf cells of many leafy liverwort species contain oil bodies (visible when magnified 100x-400x), whereas those of mosses do not.

Most moss species have persistent sporophytes with sturdy stalks (setae), and generally more complex urn-shaped capsules with teeth around the opening (peristome) to aid in spore dispersal.

In contrast, liverworts have rather transient sporophytes with flimsy setae, and with a simple spherical capsule, which opens along four lines of dehiscence like a banana, or by simple fragmentation.

More about liverwort sporophytes on the unifying characters page.

How can you tell a liverwort from a hornwort?

Hornworts have sporophytes which consist of a horn-like capsule, in which the spores are produced. The “horn” splits open to release the spores once they have matured.

In contrast, liverworts have sporophytes which consist of a spherical capsule in which the spores are produced, which is oftentimes atop a flimsy stalk resembling a glass noodle. Upon maturation of the spores, the spherical capsule opens along four lines of dehiscence like a banana, or by simple fragmentation. (See previous photo)

The thin but juicy thallus of hornworts appears to be somewhat translucent, like a green gummy bear pounded mostly flat. In contrast, most complex thallose liverworts have a significantly thicker, meatier and clearly more complex thallus, with the upper surface often dotted with air pores, the lower surface typically covered with scales, and frequently with distinct male and female structures.

The complex thallose liverwort in this photo, a Riccia species, is a bit trickier to identify as such because it lacks air pores and any additional external structures. If you examine it closely with a hand lens you will see that it is significantly thicker and more opaque than the hornwort next to it.

Hornworts should be easily differentiated from leafy liverworts with their stems and leaves, and from bottlepore liverworts with their balloon-like involucres. What about the simple thallose liverworts, though?

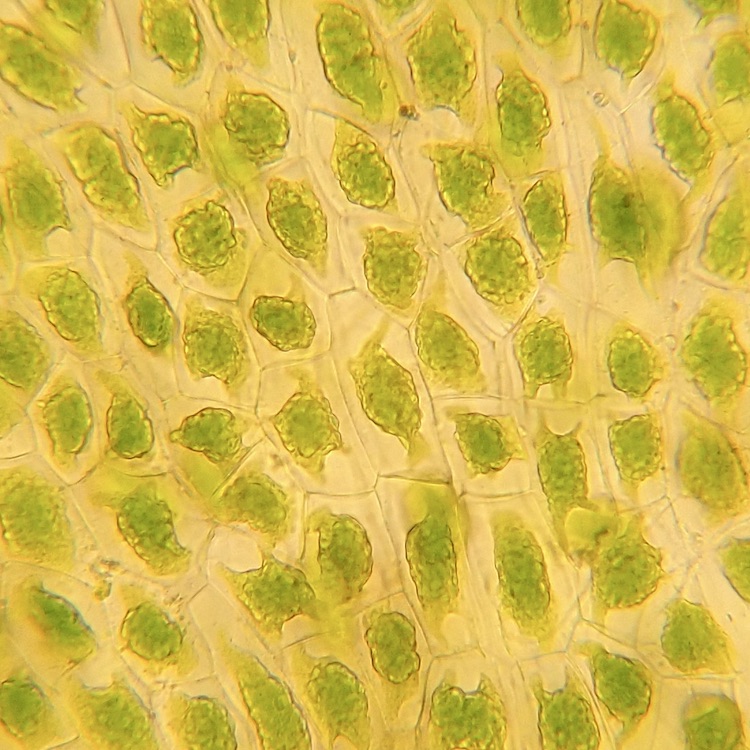

In the absence of sporophytes, some simple thallose liverwort species can closely resemble a hornwort, looking rather gummy and translucent. The most surefire way of distinguishing between the two is to look at the chloroplasts within the cells, using a compound microscope. Hornworts have very large chloroplasts, generally 1-2 per cell.

Liverworts, in contrast, have many smaller chloroplasts per cell.

I had been hoping this hornwort was the simple thallose liverwort, Pellia neesiana, which had been reported previously at a site here in Santa Barbara County. Alas, on closer inspection, it had the signature few giant chloroplasts per cell of a hornwort.

Our only local representative of the simple thallose liverworts, Fossombronia longiseta, is rather different than most, and is easily recognized by its lettuce-like look. Here, you can see that it is much thinner and frillier than the gummy hornwort it is growing amongst.

Liverworts, hornworts and mosses, collectively known as the bryophytes, tend to occupy the same ecological niche, so you will often see them growing side-by-side and intermixed.

Here in Southern California, mosses are by far the most common of the three, and hornworts the rarest, with liverworts falling in between.

In our area, hornworts grow pretty much exclusively on soil, or sometimes on thin soil over rock. Mosses, in contrast, may be found on soil, on rocks and boulders and on trees and shrubs. Liverworts are most common on soil, but some species will also be found on shaded rocks and boulders, and some may grow on the trunks and large limbs of trees and shrubs.

How can you tell a liverwort from a lichen?

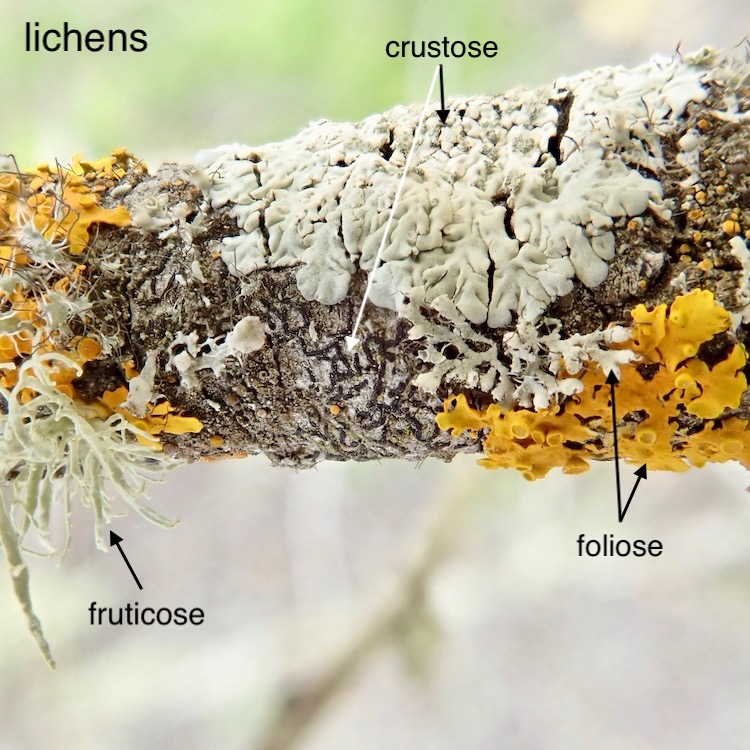

Lichens are composite organisms composed of a fungus, an alga and/or cyanobacterium, plus oftentimes a yeast. Lichens have an even wider variety of morphologies than liverworts, with fruticose, foliose, crustose, leprose, squamulose, jelly forms and more, making comparisons difficult.

Lichens also come in a wide variety of colors – red, orange, yellow, green, grey, brown, black, white – many of which are brilliantly bright.

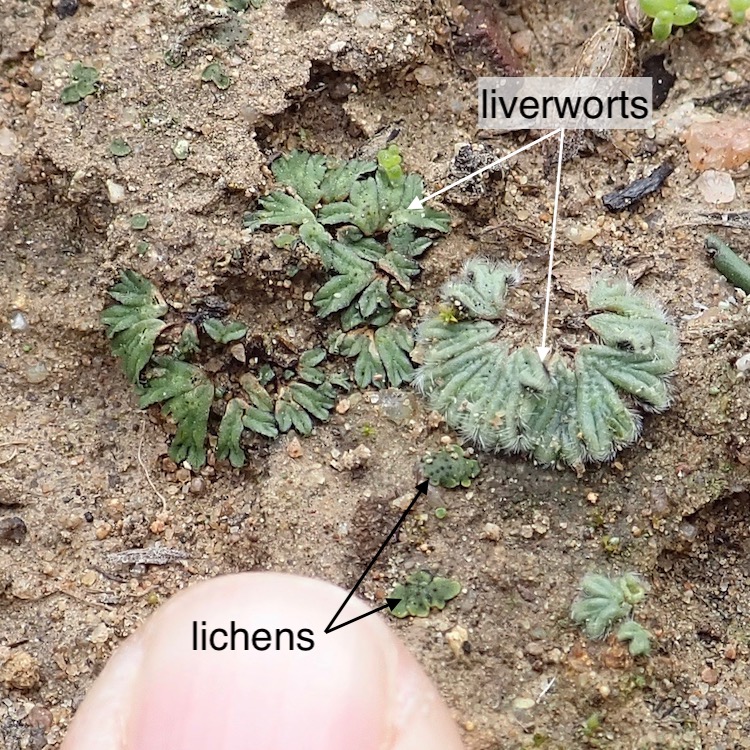

In contrast to lichens, liverworts have a more restricted palette, and generally come in shades of green, with some species turning a bit orange or reddish-purple to nearly black when growing in an exposed habitat. Some liverwort species can be so light green as to appear whitish or greyish.

In general, lichens have a stronger, tougher structure than liverworts, with an almost papery feel to the thinner foliose varieties, and a more stick-like feel for the fruticose varieties, at least when dry.

Liverworts tend to have a thicker, softer, juicier, meatier feel and can be easily dented or even cut with a fingernail.

Lichens tend to look very similar when wet or dry. They are often a brighter color when wet, and have a softer more pliable texture, but retain the same structure. Foliose lichens like this one tend to have a papery feel when dry.

In contrast to lichens, liverworts tend to look quite different when dry. Many species shrivel and look downright hideous when dry, and others all but disappear.

Notable exceptions to this rule are some of the leafy liverworts, which tend to look crispier when dry but have the same overall general appearance. However, these liverworts have an obvious stem with leaves and lichens never have stems with leaves. Mosses, which also have a stem and leaves, also look quite different when dry than when moist.

Most of our larger, more noticeable liverworts here in Southern California are found on soil. Some of the more common (or again, larger and more noticeable) lichens which grow on soil here are in the genus Cladonia. These lichens have a primary thallus which consists of chip-like squamules, and a secondary thallus which consists of trumpet or horn-like podetia. Both primary and secondary thallus are much harder and stiffer than any liverwort thallus. Consequently, when the liverwort thallus dries, the margins roll in and it becomes a greasy black string. In contrast, the lichen remains pretty much the same.

Here is another example of a lichen in the genus Cladonia growing on soil with its rather crispy squamules and stiff horn-like podetia. There is a tiny bit of the frilly liverwort Fossombronia longiseta growing amongst it – see if you can find it.

The fruiting bodies of lichens tend to be round and disk like, oftentimes a different color than that of the main body of the lichen.

In contrast, the “fruiting bodies” or sporophytes of liverworts consist of a spherical capsule, often on a watery stalk.

Some liverwort species have gemmae cups which may superficially resemble the fruiting bodies of lichens in that they may be circular, but they are typically green and are filled with disc-shaped gemmae.